|

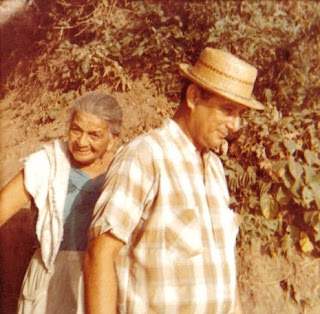

| With my maternal grandmother in a picture taken some 50 years ago |

That night I was too little to comprehend the reasons why my father would flatly refuse to attend parties of any kind, save for the occasional family gathering. Half a century after being there, propped up by him to the windowsill so that I could also watch the people dancing, my recollection goes back to how fortunate I was that my father [with my maternal grandmother on the pix above] was treating me like a grown up, as I was actually [but not really] going to the town dance. The delight was even greater on realizing that none of my other friends was there.

He was hardly against socializing and enjoyed bantering and shooting the breeze as much as anybody. But the setting had to be the right one. When little, me or my brothers would literally roll on the floor at the jokes he told. Looking back, I realize that it was not so much what he said but how he said it. Best of them all was his gesturing when performing the onomatopoeic rendition of the misadventures of this poor feline that fell into a well.

The urges of the hen and the duck notwithstanding, its caterwauling for help was futile, especially after the goat proclaimed: "Baaaaad karma, kitten! You're buggered!" [It's more profane and certainly funnier, depending on who tells it, in the original version, trust me. You can read my versions of the jokes he told both in English and in Spanish.]

Years later, when I grew up, I had the answer to why his dislike for parties: sometime during his youth, never knew if during his service as a National Guardsman or back when he had been to Panama, for example, he took to drinking. Binge drinking, that is. He would stay away from the sauce for months, even years, and then, one day, slip and fall. Eschewing parties was avoiding temptation.

This wonderfully gregarious and happy man was still there when the demon of alcoholism besieged him. You knew he was still around. Even then, despite my lack of understanding why he did that, I knew that his sickness was a reflection of his sorrows, whatever they were. Don't know quite well how to summarize it but here it is: his affliction reflected a man with feelings, not just one burdened with an addiction.

That night at the party — and I don't recall having it happened at any other time— I was actually amazed to hear my father ask the marimba band leader and also the town barber, to play this one song that spoke of a long lost love. Couldn't ever tell if it was in fact that he actually missed a woman or just happened to like that song. His emotion was so raw and intense that I always thought my asking would have been an intrusion.

It was not until some 20 or so more years after that night, when I confessed to my mother how difficult it was for me "to get her [my future wife] out of my mind," that I would come to understand why at such a short age I had been able to gauge the strength of his emotion — things, by the way, have changed a lot since then and in time one learns to do away with memories, so the preceding phrase should only be read in the context of what once was.

By then it was the mid-1970s and for the first time ever I had seen my father cry. At the town cemetery where tío Roberto was being buried I climbed atop a wall to shoot pictures of relatives and friends attending the funeral. Panning the area, the camera lens showed me far from the rest by one of the mausoleums this man with slumped shoulders, grief overcoming him, that sobbed almost uncontrollably trying to hide his pain.

Not physically as close as we had been back then at a more joyous occasion, both Payito and me were again together emotionally bonded —on the outside, looking in.

No comments:

Post a Comment