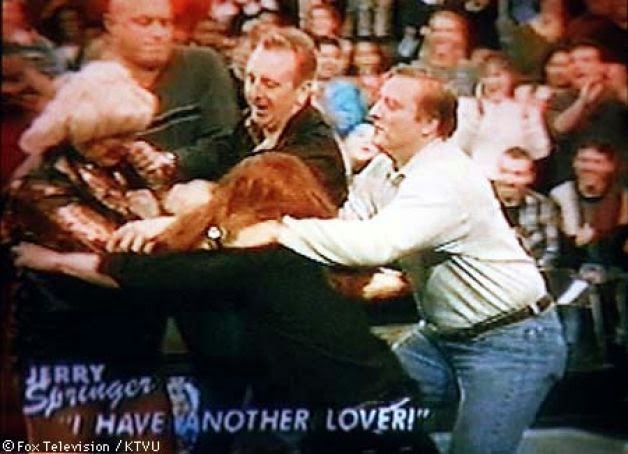

To be fair, in decrying the allegedly negative influence of soccer on U.S. morals the columnist did not refer specifically to either audience [the pix here is taken from this blog], though a few days after her first column she did reiterate that football lacks the required toughness to make it a sport.

|

| Fighting against moral decay |

“The only risk of death in a soccer game,” says she, “is when some Third World peasant goes on a murderous rampage after a bad call.”

An assertion that will undoubtedly bring peace of mind to the families of hundreds of victims of murderous rampages all over the United States: "Don't you worry none, granny! It ain't like they were watching a soccer game, they were killed yonder at [please make a selection]:

a) the movie theater

b) the outdoor music festival

c) the High School nearby!"

However unscientific or, well, stupid her “finding” about Third World murderous peasants may be, we can all rest assured that there have been tragedies during football games — not all, however, as a result of bad calls.

Because human nature is the same wherever you are, the tragedies have happened in cities such as Lima, Peru, 50 years ago last May, or in other backward Third World places such as Brussels, Belgium, or Bradford, England — these last two mind you within a span of only 18 days in May 1985.

As for blown calls, they happen in any sport and any place in the world including, yes, horror of horrors, the United States.

At least until the ESPN broadcasts of the 2014 FIFA World Cup from Brazil, there used to be a difference about how sports narrators and commentators in the U.S. tackled bad calls.

While referee mistakes have been always reported and subject to analysis [be it instant or post-facto analysis] seldom have they been portrayed in such a way as to practically blame the officials for whatever happened on the field of play.

Sadly for sports fans and athletes in most Latin American countries — could very well be the case in other regions —, blaming the official is kind of the expected behavior from sports narrators and analysts: you may forgive their lack of technical knowledge or their inability to correctly call the game, but woe to them if no mention is made of misdeeds by referees or linemen.

Advances in technology such as instant replay and practically a myriad of alternate shots of the action have only accentuated that negative quality in sports narration and commentary in Latin America.

That was not the accepted practice in the United States, where players, coaches and managers, as well as administrative staff of professional clubs can be fined for criticizing referees.

The one strong reason why blaming the referee was not the accepted practice by U.S. narrators and commentators was this simple fact: while one may have the leisure of coldly analyzing a replay, the referee has but just one split second to decide.

At the speed with which the action develops nowadays, it may sometimes feel like a nanosecond.

In turn, that makes it unfair to go hellbent on the official’s decision, so as to supposedly magnify your reportorial acumen.

That, in my opinion, has changed for the worse in the ESPN narration and commentary during the Brazil 2014 World Cup games.

Soon after the conclusion of the Mexico-Netherlands game, an irate ESPN narrator went as far as to argue that the penalty call against the Mexican national team was wrong, because the rules estipulate that there has to be the intention of bringing a player down so that a foul will be called. [I have used bold type to avoid the quotation marks, since I don’t have the exact quote with me.]

Because the rule is even harsher [“a direct free kick will be awarded if a player … trips or attempts to trip an opponent”] the distortion by the narrator cannot be more blatant.

You have to notice also that in prefacing the listing of the first seven of ten offences which will result in a penalty kick, the rules also say that the sanction will be imposed if they are committed “in a manner considered by the referee to be careless, reckless or using excessive force.”

In the — again — split second the action developed, the referee had to decide whether an "offence" [to use the British spelling adopted by FIFA] was committed, taking into account all the above mentioned criteria.

The matter goes beyond a simple disagreement with an official's decision or an inadvertent or willful distortion of the rules just to make a point that will reinforce your position.

Not a few days after the controversial penalty call, another of the ESPN commentators went so far as to say, while broadcasting a different game, that the injury suffered by Brazilian star striker Neymar while playing Colombia was due to the lax enforcement of the rules by the referee in turn. [It may have been a willful foul by the Colombian defender but all replays shown by ESPN appear to show that his intent was not, certainly, to disable the Barcelona player.]

The commentator then added, using the tone of voice that will make the audience think that he was being clever and had the right amount of cheek, that he had been remiss in just saying "the referee" and not mentioning him by name, which he then proceeded to do.

Quite clever, indeed.